Governments across Canada are tackling the critical housing shortage while also addressing the climate crisis. We have a generational opportunity to build not just more housing, but to ensure all Canadians live in safe, healthy, climate resilient homes that are affordable to heat and cool. Once operational, buildings emit up to 65 per cent of municipal emissions, but carbon is built in long before the lights are turned on. As buildings become more energy-efficient and rely on cleaner energy sources, the emissions produced during operation (like heating and cooling) will reduce making those built-in carbon emissions all the more prominent in the overall carbon footprint of buildings.

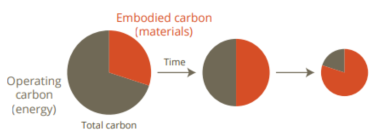

It's critical we recognize that a building’s lifetime worth of carbon starts with the materials used to build it. The emissions that come from manufacturing, transportation, construction, and disposal of building materials are known as embodied carbon. As buildings become more energy-efficient, embodied carbon will constitute a larger portion of their carbon footprint, as illustrated by Figure 1. Building new and retrofitting existing buildings with lower carbon or recycled materials can help reduce that lifetime of emissions.

Canada is already showing leadership in addressing embodied carbon through its Federal Standard on Embodied Carbon, and there are opportunities for all orders of government to do more. Treasury Board's Standard on Embodied Carbon mandates a 10 per cent reduction of concrete used in government projects and requires disclosure of concrete’s carbon footprint of ready-mix concrete on construction projects. Governments should expand these efforts by setting project-scale embodied carbon targets.

Similarly, British Columbia's Minister of Housing recently announced updates to the B.C. building code to allow for greater use of mass timber in buildings. Embracing new opportunities to use mass timber in taller buildings, and in more building types, signals a positive shift towards greater use of lower carbon materials. Choosing materials with low embodied carbon, or those that sequester carbon, contributes to creating highly efficient, climate-resilient homes and buildings, while mitigating the environmental impact of construction.

In June, we’ll be putting out our Carbon-free Concrete: Building a net-zero foundation for Canada report, in which we show that not only embodied carbon limits are needed, but also governments must fund the development of environmental product declarations (EPDs). EPDs leverage data from life cycle assessments to determine the carbon intensity of building materials, verifying the overall embodied carbon of a building and allowing designers make informed low-carbon material selections. We also find that strategic government procurement is needed to stimulate market demand for made-in-Canada lower carbon building materials.

Governments across Canada have a generational opportunity to ensure new housing is safe, healthy, climate-resilient, and affordable to heat and cool. As operational emissions decrease with clean energy, the importance of embodied carbon grows. Setting ambitious targets, supporting low-carbon materials, and funding Environmental Product Declarations are key steps. As Canada addresses the twin crises of housing shortages and the climate emergency, all orders of government must implement coordinated green building policies and reduce embodied carbon in building materials to address lifetime carbon emissions.

Note: this blog was edited in July 2024 to update the title of the Carbon-free Concrete report.