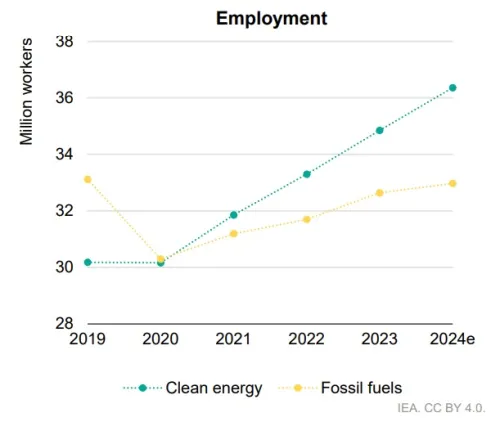

The latest World Energy Employment report by the International Energy Agency shows that, globally, jobs in clean energy are growing at 3.8%, faster than the rest of the economy, which grew at 2.2%. This trend is expected to continue. While this is good news for Canada, we cannot expect these jobs to appear in this country without concerted effort.

The IEA's report highlights how energy jobs increased by 2.5 million around the world in 2023. Clean energy jobs grew at a significantly larger scale than those in the fossil fuel sector, which are expected to taper off as the global demand for these fuels declines in the 2030s. Meanwhile the rapid electrification of energy systems will lead to continued job growth over the next several decades. The report notes that if the world achieves net-zero emissions by 2050, far more jobs are created when compared to the status quo where no additional climate or clean growth policies are implemented.

What are clean energy jobs, exactly? These can be jobs in construction, manufacturing, raw materials, trade, wholesale, professional services and utilities that support clean power, buildings, and transportation sectors. The Pembina Institute’s analysis shows there could be two million clean energy jobs by 2050 in a net-zero emissions scenario. Considering the pace of clean growth, impending retirement booms and a tight labour market, the demand for skilled workers is greater than ever before.

As the IEA report suggests, skills shortages pose a threat to Canada’s ability to maximize gains from clean growth opportunities. When there are not enough skilled workers, projects may not be delivered on time or on budget, or even initiated in the first place. This phenomenon is already visible in Canada’s building sector where labour and skills shortages are slowing down critical housing projects. Skills and labour gaps are cited as a core issue behind slow productivity, lost business opportunities, and nearly $50 billion in unrealized GDP over the last 20 years. These problems have contributed to the growing affordability crisis.

IEA researchers interviewed 190 energy employers around the world, and the vast majority experienced challenges hiring workers across all categories of work. Countries that get ahead of addressing labour market issues will have a competitive advantage in attracting clean energy investment.

Governments and employers around the world are investing in programs designed to grow the available pool of workers and providing more on-the-job training. In the United States, new apprenticeship grants amounting to $200M USD and mandatory apprenticeship quotas for projects initiated via the Inflation Reduction Act are already demonstrating efficacy, with a 44% increase in registered apprentices over the last five years. Companies are also partnering with post-secondary institutions to collaboratively design courses that respond to labour market and industry needs.

Canada has adopted labour requirements as part of new clean energy tax credits and made investments in training capacity via the Sustainable Jobs Training Fund. However, more innovative thinking and a coordinated approach among labour, government, and post-secondary institutions is needed to align our training system with the emerging workforce demands of a clean economy. This means: 1) increasing the number of skilled workers; 2) upskilling workers for new opportunities, and 3) offering the kind of work that attracts people to it: good, decent jobs that support communities and families.

The IEA has called this the “age of electricity.” As with major energy shifts of the past, there are major opportunities for workers. The question for policymakers now is: will Canada rise to the challenge?