In order for Canada to achieve its climate targets and mid-century decarbonization goals, emissions from existing buildings must be significantly reduced and construction practices must rapidly evolve to reach net-zero ready standards for new buildings.

Current policy direction among all levels of government in Canada assumes a shift toward net-zero energy ready construction for new buildings by around 2030. For example, the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change calls for the adoption of a net-zero energy ready model building code by 2030. The provinces of Ontario and British Columbia have committed to adopting similar requirements by 2030 and 2032, respectively, and the City of Vancouver is requiring new construction to be zero carbon emissions by 2030.

Shifting new construction to net-zero ready by around 2030 will lead to a significant reduction in emissions from new buildings, but will not be sufficient to achieve deep emissions reductions in the building stock as a whole. In B.C., for example, it is estimated that this will result in less than a third of the reductions needed in the building sector by 2050. Therefore, the federal government will need to work with the provinces to create and implement a comprehensive strategy for existing buildings.

Setting a vision for a decarbonized building sector by 2050 offers a clear, achievable guiding principle and a consistent approach for sub-national governments to follow. A vision for Canada’s building stock that delivers on climate commitments is one that sees an evolution to ultra-energy-efficient construction, deep energy retrofits and switching to low-carbon fuel sources. While supporting measures such as financing, incentives, energy labelling and voluntary programs are critical measures for market transformation, deep emissions reductions in the building stock by mid-century are not likely to be possible without an ambitious and clear pathway set through codes and regulations. Responding to this need, The Pan-Canadian Framework has committed to the development of a national model code for existing buildings by 2022.

Model regulations for existing buildings

Provincial and municipal building energy codes in Canada typically make reference to one or more external standards, with modifications as necessary to meet the unique needs and goals of each jurisdiction. The most commonly referenced whole-building standard in Canada is the National Energy Code for Buildings (NECB), published by the National Research Council and intended as a model code, meaning that it is intended to be adopted by authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs), but has no legal authority in its own right.

Model code development process

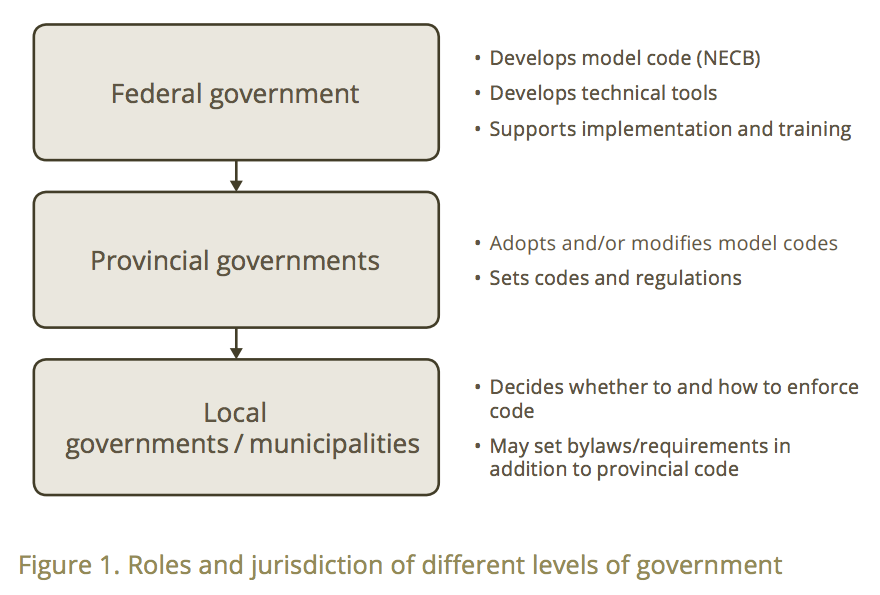

The development of model codes in Canada, including the NECB, is undertaken by the Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC), a committee established by the National Research Council. Model codes developed by the CCBFC are modified as necessary by provinces, territories, and other AHJs, and become enforceable building codes in those jurisdictions. There is typically a delay of several years between the release of a new version of the model code, and the adoption of those revisions by AHJs. Figure 1 shows the roles of different levels of government in code development.

The development of code requirements for existing buildings will be a complex task that will cut across the mandate of several of CCBFC’s Standing Committees. An existing building energy code will need to consider a “whole-building,” holistic approach to energy efficiency and carbon reductions, and should be developed with the expertise of a broad group of stakeholders. Some of the specific issues that will need to be considered are discussed below.

Triggers

Retrofit requirements could be triggered at time of renovation, time of sale, or based on performance; there are advantages and disadvantages to each method.

A time of renovation approach offers the advantage of leveraging work already being done, and reducing the incremental cost of compliance. However, time of renovation requirements may encourage building owners to defer capital investment, or to conduct upgrades without permits.

Triggering enforcement of energy code compliance based on the relative performance of a building is often referred to as a Building Energy Performance Standard (BEPS), and requires pre-existing information on the energy performance of the building stock (benchmarking). BEPS promises smart regulations that achieve significant carbon reductions by targeting the worst performing buildings first. This is also, in a sense, the main weakness of the approach; buildings might underperform because owners lack the means or the knowledge to invest in these buildings.

Requirements triggered at time of sale would tie code compliance to a transfer of ownership. Such an event provides a clear opportunity to require compliance, just as time of listing is used in some jurisdictions to require energy use labelling and disclosure. However, unlike energy labelling, energy code compliance may require substantial alterations, placing a financial burden on the buyer that would need to become part of the overall valuation of the property.

Compliance

Traditional building codes are prescriptive; that is, they define the minimum standard that each building component must meet. An example would be a requirement that a wall assembly meet a certain R-value. While prescriptive codes have the advantage of being relatively easy to implement and enforce, they do not incorporate models of how the entire building performs as a system, and therefore do not always prescribe the most efficient, cost-effective or flexible solutions.

Performance-based codes differ from prescriptive codes in that they do not mandate the use of certain materials, assemblies or methods, but rather define the desired overall performance level of the building. Performance-based codes are rising in popularity as computer-aided energy modelling becomes more widespread.

Performance-based codes can be more complex to implement and verify due to the need for energy modelling, and sometimes for post-construction verification tests (e.g., a blower door test for airtightness). However, they offer the advantage of greater flexibility and efficient use of materials, sometimes leading to significant cost savings when compared to prescriptive pathways.

Enforcement

Although many provincial building codes technically apply during alteration of buildings, enforcement of codes is often not observed for retrofit projects, leading to unpermitted, informal, or otherwise “underground” activity. Building owners may also choose to defer planned investments in their buildings due to a fear of triggering extensive requirements under the building code.

The current lack of enforcement by AHJs in both new construction and retrofits is partially due to a systemic lack of adequate resourcing for those jurisdictions. Therefore, a national retrofit strategy must begin to address the funding and capacity-building needs of cash-strapped municipalities that have limited capacity to enforce codes.

Adequate support must also be given to the building industry in the form of training and the sharing of best practices. Only with this support will ultra-energy-efficient construction become entrenched within the industry as the “new normal”, thus making compliance with more stringent codes feasible and acceptable.

Other components of a retrofit strategy

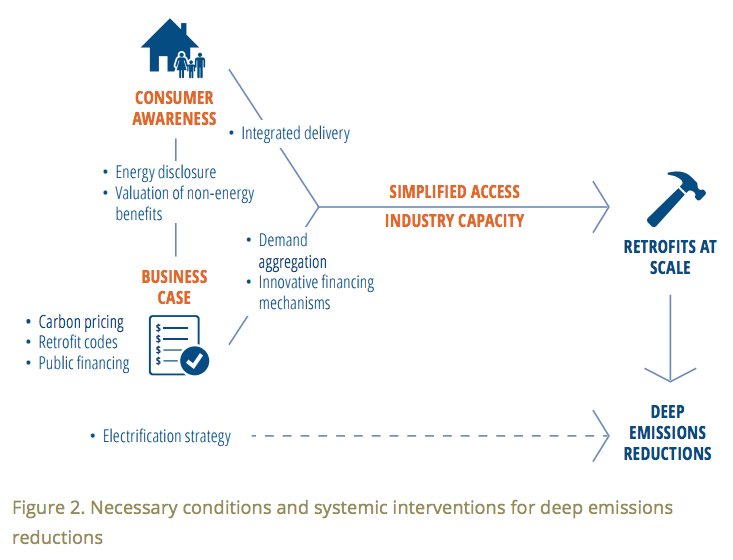

Although the development of codes by federal and provincial governments is a critical step in ensuring that the building sector meets decarbonization goals, codes are only one part of a holistic strategy. A comprehensive retrofit strategy for Canada is one that encourages market transformation and offers consumers and industry the tools and support needed to make regulations successful.

The Pan-Canadian Framework commits to improving energy efficiency standards for appliances and equipment. Several building components that might be covered under appliance and equipment standards (e.g. windows, boilers, heat pumps and light fixtures) have a large impact on the overall energy performance of a building. Strengthening the stringency and coverage of equipment standards may ease the administrative burden of code enforcement by ensuring that key components are already mandated to be highly efficient under separate regulations.

Benchmarking, labelling and disclosure policies are foundational tools in enabling an energy code for existing buildings. Voluntary programs have existed for a number of years, and have allowed industry capacity to develop. However, to advance market transformation and collect data for regulatory design, the reporting and disclosure of energy information must become mandatory.

Although previous federal incentive programs such as the ecoENERGY Retrofit program have been successful, maintaining the level of effort required to decarbonize Canada’s buildings stock by mid-century will require a sustained effort and long-lasting programs.

There are multiple ways in which publicly raised capital could be used to accelerate retrofits, including the use of a centralized public financing authority (e.g., the Canada Infrastructure Bank or the proposed Ontario Climate Change Solutions Deployment Corporation), focused on energy efficiency and building renewal. The use of public funds to leverage private capital allows for a much larger and more sustained effort.

Innovative repayment and credit enhancement mechanisms aim to encourage longer-term financing, increased loan security and lower interest rates. Repayment mechanisms include local improvement charges (LICs), utility on-bill financing (pay-as you-save), energy service agreements, equipment leases and soft loans. Credit enhancements include loan loss reserves, loan guarantees and interest rate buy-downs.

Providing these services can help to cover some of the initial capital outlay required to upgrade a building or bring it into compliance, while ensuring that more stringent building regulations are not regressive, and that all home and building owners have access to low-cost financing for the purpose of energy upgrades.

Conclusion

Developing and implementing code requirements for existing buildings will require a significant effort and collaboration across a wide range of industry stakeholders. These requirements must be ambitious and present a clear pathway to deep emissions reductions in Canada’s building stock by mid-century. At the same time, they must be fair and enforceable, and supported by programs to minimize financial and administrative burdens on building owners and municipalities. A model code itself has no authority unless adopted by a sub-national jurisdiction, therefore policymakers at all levels of government must collaborate in order for these requirements to be successful.

Code requirements for existing buildings are only one part of a holistic strategy for transforming Canada’s built environment. Code development at the federal level must fit into an overall strategy for existing buildings, one that addresses equipment performance standards, financing, training and capacity building, and the valuation of non-energy benefits.

Dylan Heerema is an analyst with the Buildings and Urban Solutions Program at the Pembina Institute, a Canadian clean energy think-tank.

This article appeared in the October–November 2017 issue of Building magazine.