This week or next, the federal cabinet is expected to decide on the fate of the Petronas-backed Pacific NorthWest LNG proposal near Prince Rupert, British Columbia. One of the issues central to their deliberations will be the carbon pollution arising from the project. The B.C. government is advocating for the project to be approved as is. Unfortunately, the province’s advice ignores two major failings of the project — flaws that will undermine Canada’s commitment to the Paris climate change agreement and set a terrible precedent for other liquefied natural gas proposals.

The first failing is that the project is proposing to rely on wasteful technology — even though better alternatives exist today and are incorporated into the designs of a similar project just over 100 kilometres away. As proposed, Pacific NorthWest LNG will rely entirely on burning natural gas for the liquefaction process. The LNG Canada proposal (backed by Shell) is proposing to use a mix of natural gas and electricity — an alternative that could be 41 per cent less polluting. The project is similar in size, has similar timelines and is located in nearby Kitimat.

There’s no excuse to allow Pacific NorthWest LNG to proceed with sub-standard technology. The site is a mere 10 kilometres from the electricity grid. According to B.C. Hydro’s resource options map, the site is surrounded by renewable energy opportunities.

The second failing is the lack of a plan to improve the project’s performance over time. As proposed, the first phase of the project won’t see any improvements in its 30-plus years of operation, and there’s no guarantee that the second phase would be any better than the first. In both cases, much better is possible. The first phase could rely increasingly on renewable electricity as it becomes available, and there’s enough time for the second phase to rely entirely on electricity in the same way that Woodfibre LNG, near Squamish, is proposing to do. There are legitimate reasons why that level of performance isn’t possible right now, but there’s no good reason to lock in the limitations of today until mid-century.

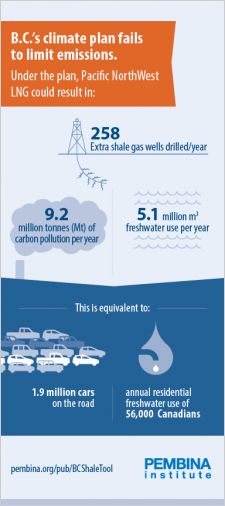

Given the scale of the project (the export terminal would cost $12 billion to build), the environmental implications of these failings are significant. As proposed, the facility could emit up to 4.9 million tonnes of carbon pollution per year. That’s equivalent to over one million cars on the road (and this doesn’t include the shale gas operations in northeast B.C. that would feed project). But if the first phase was built to the standard of LNG Canada and second phase to the standard of Woodfibre LNG, the total would be 2.3 million tonnes. That’s still a major increase in carbon pollution when we need their levels to drop, but it’s also materially better than what’s currently on the table.

How could these failures be allowed to happen? Part of the problem stems from two policies implemented by the B.C. government. In 2014, instead of mandating a high level of performance, the province’s carbon rules for LNG offered up several compliance loopholes that gave proponents options to pay for credits instead of actually limiting their pollution. Then in 2015, the province made things worse by signing a long-term agreement with Petronas that promises the Malaysian state-owned enterprise compensation if any future provincial government tightens those regulations.

The federal government shouldn’t be constrained by B.C.’s poor policy decisions, but to date the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency hasn’t shown a willingness to push back substantively on the project’s failings. It looks like that task will fall to the federal cabinet as they make their determination.

If cabinet doesn’t push back and allows the project to proceed largely unchanged, the federal government will be sending all the wrong signals. They’ll be signalling to B.C. that it’s okay to miss legislated climate targets that are supposed to be part of a national climate plan. Other provinces will see the same signal as will the international community in the lead-up to the Morocco climate negotiations in November. They’ll also be signalling to Petronas and other LNG proponents that Canada is fine with substandard technology that doesn’t improve over time.

If “Canada’s back” is going to be more than an empty slogan, all of the signals need to be the right ones. Thankfully, the federal government has the full ability to do so and not allow the mistakes of B.C. and Petronas to be locked in for the next 30-plus years.

This article originally appeared in iPolitics.