Herald columnist Deborah Yedlin criticized the Pembina Institute for, on the eve of the 10th anniversary of the watershed Syncrude ducks incident, daring to point out that the issues with oilsands tailings have demonstrably worsened over the past decade and deserve ongoing coverage and attention.

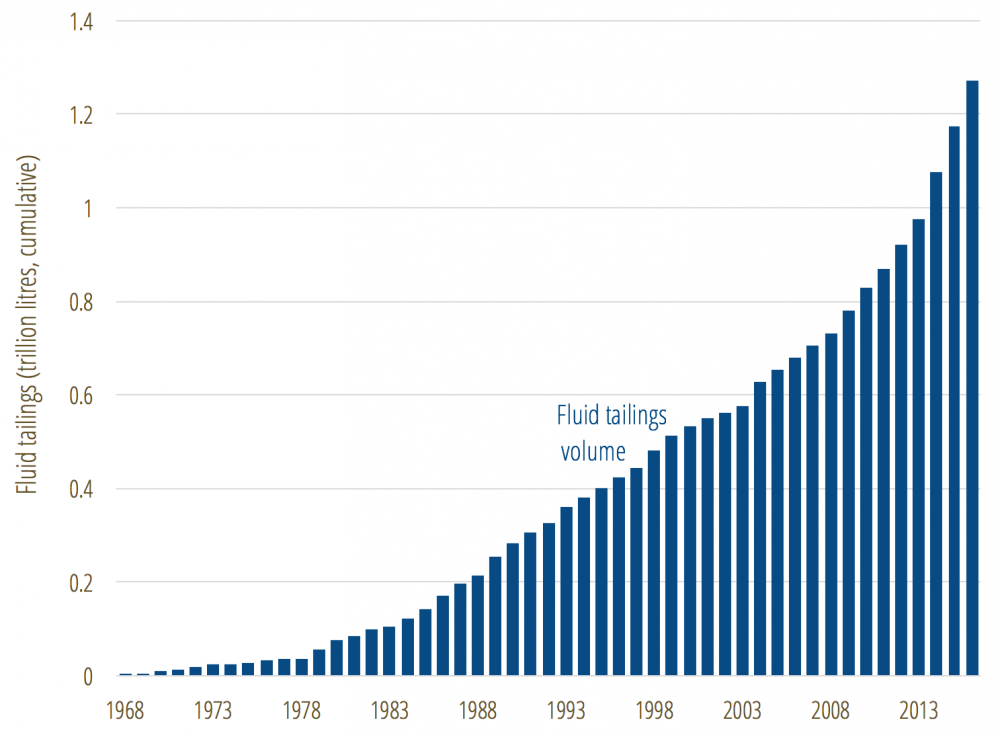

The incident catapulted the much broader economic and environmental risks posed by Alberta’s tailings ponds to the national stage. In 2008, the ponds had already been growing for 40 years with virtually no regulatory oversight.

In response to the increased awareness and public pressure, by 2010, then-Premier Ed Stelmach assured Albertans the regulator was going to “aggressively” crack down on the industry. Premier Alison Redford echoed these statements in 2013, stating “tailings ponds will disappear from Alberta’s landscape in the very near future,” and that their growth will “completely halt by 2016.”

The work of Canada’s Oilsands Innovation Alliance is valuable; industry collaboration on this challenging issue is critical and should be encouraged. However, this is not a substitute for firm rules to hold the industry accountable.

Figure 1. Fluid tailing ponds volume growth since 1968

Despite industry talking points, meaningful progress on tailings management is elusive. Directive 074 was an abject failure – all operators failed to comply with the rules, and rather than enforcing them, the regulator scrapped the regulation altogether.

The new Directive 085 has not delivered, either. Based on the sum of the plans submitted, tailings volumes will continue to grow by another 300 billion litres over the next two decades. Further, almost every operator proposes treating tailings by pumping them into mined-out pits and placing water over them to create permanent “lakes.” This unproven approach poses significant risks and will have long-term consequences for ecologies and communities.

Finally, the 10-year reclamation timeline Yedlin cites requires operators to merely deem their still-fluid tailings inventories “treated” by their own criteria. Two operators planning to shut down operations in the early 2030s have proposed reclamation timelines that extend beyond 2100 — 70 years after their mines close and revenues to fund reclamation have ceased. Pardon our skepticism.

What may concern Albertans most is that the province holds less than three per cent of the expected costs to clean up oilsands mines in securities. If major companies are not around when these sites are reclaimed in coming decades, taxpayers could be left on the hook for at least $27 billion, according to estimates from the Alberta Energy Regulator.

The unsecured cleanup bill for tailings ponds is all the more relevant considering the recent spike in oil and gas bankruptcies that have left landowners with abandoned infrastructure on their property. In the 2016 Redwater case, the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench ruled in favour of allowing the company’s creditors to pocket the profits from remaining assets and offload reclamation liabilities for the government to deal with.

While the decision is currently being appealed at the Supreme Court, several companies have already followed suit – including bankrupt Sequoia Resources Corp., which threatens to double the inventory of the Orphan Well Association.

Pointing to similar gaps in oilsands tailings management does not make one against oilsands development, but rather, for fiscal responsibility and ensuring taxpayers are not left unprotected.

The Pembina Institute has worked with government and industry to improve environmental management in the oilsands for more than 30 years. Where progress in oilsands management is demonstrated, we are happy to acknowledge improvements in environmental policies and performance.

Where gaps remain, as in the failure to properly regulate tailings, we make no apology for providing factual performance data on this growing and under-reported issue that deserves far greater scrutiny as one of the most significant economic and environmental issues facing our province.

This article also appeared in the Calgary Herald.