Leading stakeholders in electricity system innovation gathered at the Rocky Mountain Institute’s 2017 eLab Summit in Albuquerque, New Mexico. One working group was dedicated to the electrification of heating and cooling in buildings. The Pembina Institute and the City of Vancouver participated in this meeting in order to bring lessons from jurisdictions around the world back to Canada and to contribute to the low-carbon transition that is already well underway.

This is Part 1 in a three-part series on electrification in the built environment. Read Part 2 and Part 3.

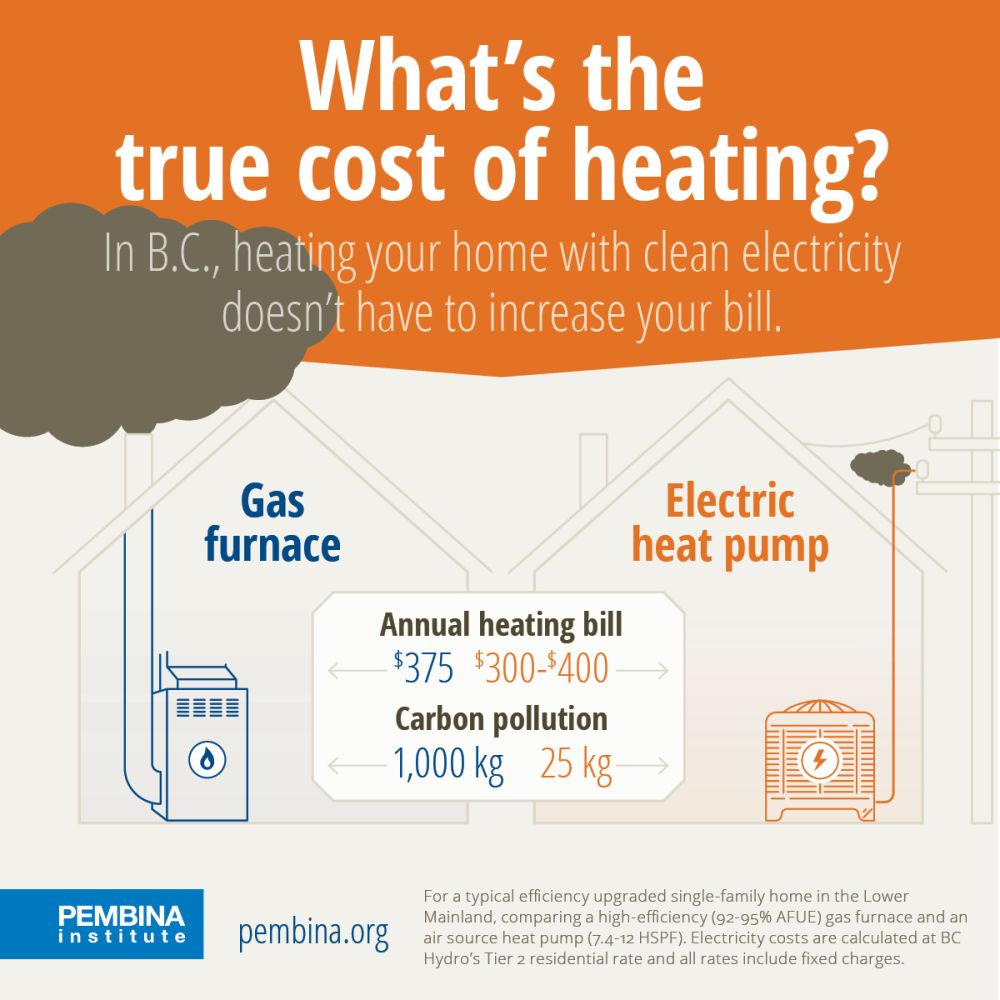

Furnaces, boilers, and other heating equipment constitute one of Canada’s largest sources of carbon pollution. In fact, the burning of fossil fuels in homes and buildings — mostly natural gas and heating oil — accounts for around 12% of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions. In order for Canada to reap the benefits of tomorrow’s low-carbon economy, we must transition away from these dirty fuels and toward emissions-free alternatives. Fortunately, solutions already exist — one of the most promising being the electrification of heating.

Electric heating technologies have been around for a long time, and in some parts of Canada electric baseboard heaters and water heaters are very common. These technologies are tried and true, and are also relatively clean, particularly in provinces such as B.C., Manitoba, and Quebec, whose supply of electricity is already low-carbon. However, these technologies are also relatively inefficient and therefore can be expensive to run, compared to popular options like natural gas furnaces. Thankfully, better alternatives exist today.

Heat pumps are the most promising alternative to fossil fuel heating for many kinds of buildings. They have been around for decades, but have only recently been perfected for use in cold climates like Canada’s. These devices are much more efficient than electric resistance heaters, and can be used for space heating as well as water heating. Unlike older devices, modern heat pumps can deliver heat instantly and operate with very little noise, making them much more attractive to consumers.

Heat pumps can also be run “in reverse,” allowing them to provide cooling as well as heating. As our homes and apartments become more efficient, with greater levels of insulation and airtightness, the risk of summer overheating increases, making the air conditioning abilities of heat pumps an important consideration for future-proof buildings.

The initial cost of a heat pump system depends on many factors, including the size, age, and energy efficiency of a home or building. Central heat pumps for space heating cost more than standalone “mini-split” systems, but can take advantage of existing ductwork for forced air furnaces. While a mini-split system may cost between $5,000 and $8,000, a central heat pump may cost $10,000 to $12,000 for a typical home, making the latter up to twice as expensive as a comparable gas furnace.

If a home or building is already heated with electricity, replacing electric resistance heaters and water tanks with heat pump technologies can lead to big electricity savings, and quickly pay back the initial investment. But replacing natural gas appliances with heat pumps is likely to result in smaller savings in many parts of Canada, where gas is significantly cheaper than electricity.

The low cost of gas remains a significant barrier to the adoption of electric heating, despite the environmental and efficiency benefits. One trend in the building industry that may help to address this issue is the increasing popularity of extremely energy-efficient buildings (like Passive House homes and apartments), which require so little energy for heating in the first place that a simple electric baseboard heater may be more than adequate, even on the coldest winter days.

Reaching Passive House–like levels of efficiency is feasible and increasingly affordable for new construction, but achieving this kind of performance is much more difficult for existing buildings. We know that many older buildings can realize big energy and cost savings through retrofits, and this should be encouraged. However, it’s unlikely that carbon emissions can be lowered to the levels we need in a cost-effective way without also switching the majority of buildings from natural gas to electric heating.

There are many benefits to electrified space and water heating — including the ability of a heat pump to provide air conditioning as well as heating, and the elimination of risks from gas and oil leaks. However, higher initial costs mean that these benefits and the carbon reductions that come with them are not enough incentive for many to make the switch. We need utilities, governments, and manufacturers to do more to encourage the adoption of these technologies and make them more affordable. In parts 2 and 3, we will explore some of these options.

The Electrifying Path to Decarbonization

A series on electrification in the built environment

- Electric heat pumps are key to low-carbon homes and buildings

- Unleashing the benefits of electrification for utilities and customers

- Electrification of buildings: A cornerstone of Canada’s low-carbon future

Dylan Heerema is an analyst with the Buildings and Urban Solutions Program at the Pembina Institute, Canada’s leading clean energy think-tank. He lives in Vancouver. Learn more: www.pembina.org

This article originally appeared on The Energy Collective on December 26, 2017.