In 2017, British Columbia introduced what might be North America’s most innovative beyond-code standard for energy efficiency. The B.C. Energy Step Code is an opt-in regulation that enables local governments to pursue improved levels of performance for new homes and buildings — creating healthier and more comfortable spaces that are more affordable to heat. It’s a promising experiment that could chart a path for the rest of Canada.

The Province created the framework in collaboration with industry, local governments, and civil society. But will local governments use it? Eight months after enactment, the answer appears to be a resounding “yes.”

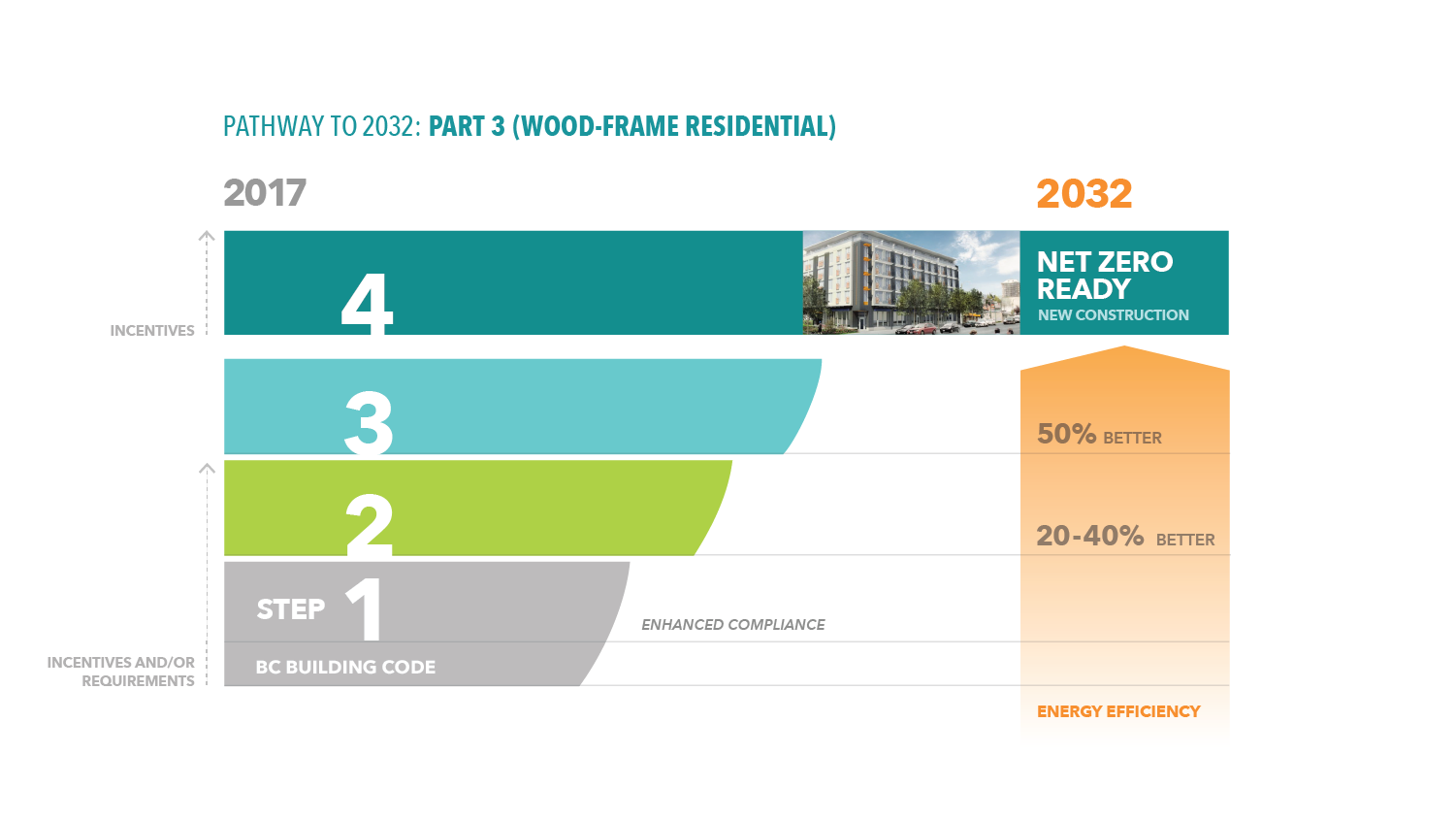

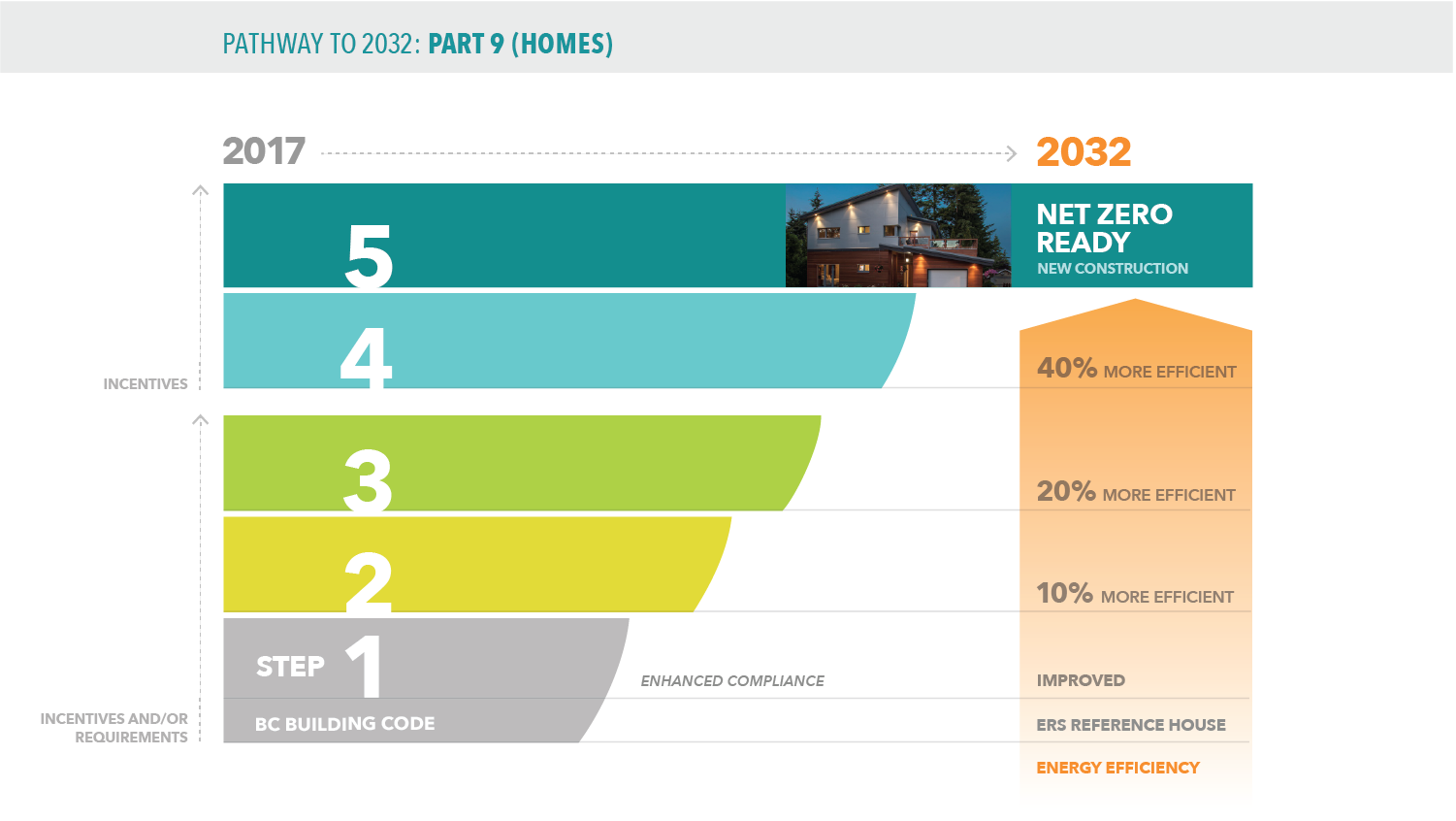

The Energy Step Code allows cities and towns in B.C. to require or incentivize one of five levels of improved building performance, from current code performance all the way to net-zero energy ready. Net-zero energy ready buildings are ultra-efficient; they could produce on-site (or nearby) as much energy as they consume over the course of a year — for example, by putting solar panels on the roof or on the canopy of an adjacent parking lot.

The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, Canada’s buildings strategy, and the B.C. Climate Leadership Plan have set targets for all new buildings to meet net-zero energy ready standards by 2030 or 2032. B.C.’s Energy Step Code is the first roadmap to achieving this goal, providing much needed clarity to the industry and to authorities having jurisdiction.

The Energy Step Code is performance-based: instead of prescribing how to build, like traditional prescriptive codes, it sets energy efficiency targets and lets the designer or builder decide how to meet them. Compliance is assessed through energy modelling software and on-site testing, greatly simplifying the permitting process and providing greater design flexibility.

Local governments step up

As of January 22, 17 municipalities in B.C. have signalled their intent to use the Energy Step Code — together accounting for over half of the province’s population. (We include Vancouver, as the City has committed to creating equivalencies between its building bylaw and the Energy Step Code.) As each municipality considers its options for incentivizing or requiring higher building performance, the question arises: At what step of the code should we begin?

An extensive costing study, completed last summer, offers some insight. It costed thousands of simulations for 10 archetypes, representing a range of possible design choices that could comply with each performance step in the six climate zones of B.C. A first of its kind in Canada, this study revealed that significant reductions in energy use, carbon pollution, and utility costs already can be achieved at very moderate additional construction costs for the first three steps. For example, the lowest capital cost designs meeting Step 3 for homes and apartment buildings in most parts of the province result in at least 20 per cent energy savings and 50 per cent emissions reductions (in some cases up to 90 per cent), for less than two per cent incremental construction costs. The designs needed to meet these performance criteria are familiar to the industry, which already regularly builds to this level under a series of voluntary programs.

Given the existence of low cost solutions and the market’s readiness, many local governments are opting to adopt Step 3, either as a requirement or as a minimum threshold for access to added density or other incentives. Metro Vancouver’s three North Shore municipalities, for example, are aligning their policies and planning to require Step 3 for new low and mid-rise residential buildings starting in July. Richmond, Surrey, Burnaby, and New Westminster are also considering requiring or incentivizing Step 3 for residential buildings.

The potential carbon pollution reductions from adopting Step 3 are significant — and make a strong case for dispensing with the first two steps in many areas. For single-family homes, for example, the marginal cost for builders and consumers of moving from Step 2 to 3 is about a one per cent increase in capital costs. Going up the step decreases emissions by another 20 per cent to 25 per cent below base code while maintaining energy costs at the same level. If all of the major municipalities in Metro Vancouver adopted Step 3 for residential buildings, over one million tonnes of carbon pollution would be avoided cumulatively between 2018 and 2030.

The introduction of the Energy Step Code also presents an opportunity to address some ongoing issue with compliance and enforcement of energy codes. Interviews with local manufacturers, builders, energy advisors, and municipal staff clarified some gaps to be addressed, but also revealed a healthy optimism about the industry’s capacity to deliver if given sufficient time to prepare and support for training. To monitor implementation, a multi-stakeholder advisory group was formed: the Energy Step Code Council. Serving as a “bridge” between the province, utilities, local governments, and industry, the council ensures coordination of training opportunities and communication of the standard.

Stepping out beyond B.C.

Such innovation need not be limited to B.C. Developing a multi-tiered framework in other Canadian provinces would allow municipalities to get a leg up and start building the industry capacity and experience required to smoothly transition to net-zero energy ready construction.

All around the country, energy efficient buildings are being built and recognized for the multiple benefits they provide, including better air quality, reduced mould and moisture, and more affordable energy costs. A national energy step code could help accelerate this market transformation. Why wait?

Tom-Pierre Frappé-Sénéclauze is the director of the Buildings and Urban Solutions Program at the Pembina Institute (www.pembina.org), and a cofounder of Three for All B.C. (www.threeforall.ca), a coalition working to inspire and inform local government action on energy efficiency through judicious use of the B.C. Energy Step Code.

This article originally appeared in the spring 2018 issue of SABMag.