British Columbia’s new government has shifted the province’s messaging on liquefied natural gas (LNG). No longer is LNG being unrealistically promoted as a once-in-a-generation opportunity for job creation, the source of billions of dollars for a Prosperity Fund, and more than $1 trillion in economic activity. Nevertheless, despite the cancellation of the controversial Petronas-backed Pacific NorthWest LNG project, LNG development in B.C. remains a complex issue that will need to be tackled by the new provincial government.

This week, the Pembina Institute and the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions published Liquefied Natural Gas, Carbon Pollution, and British Columbia in 2017, an update on the state of the B.C. LNG industry in the context of climate change. Here are three points from the report that the Pembina Institute would like to highlight.

18 LNG export projects are still eyeing the B.C. coast

No LNG export projects are up and running in British Columbia. Currently, natural gas products are produced at two small domestic LNG plants, with two additional domestic facilities proposed.

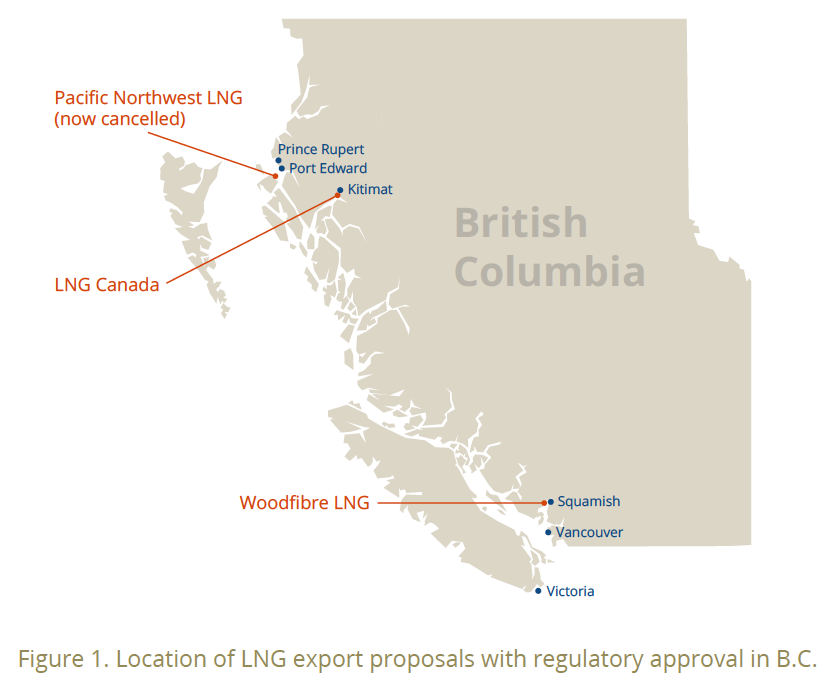

However, 18 LNG export proposals in B.C. are at various stages of development. Only two — LNG Canada in Kitimat and Woodfibre LNG near Squamish — have regulatory approval and are close to being realized. (The latter also has a final investment decision from parent company Pacific Oil & Gas.) A third approved project, Pacific NorthWest LNG in Port Edward, made headlines in July with the announcement that it “will not proceed as previously planned.”

The remainder of the LNG proposals are in the early stages of development. Most are located on the North Coast, with five projects on Vancouver Island and the South Coast.

LNG Canada + Woodfibre LNG = incompatible with B.C. climate targets

B.C. was responsible for 63 million tonnes of carbon pollution in 2014. In contrast, B.C.’s legislated greenhouse-gas reduction targets call for annual emissions to be lowered to 43.5 million tonnes by 2020 and 12.6 million tonnes by 2050. B.C. is currently on track to miss its legislated 2020 target by a wide margin, with emissions projected to increase until at least 2030. Measures in the province’s Climate Leadership Plan are forecast to bring annual emissions down to as low as 54 million tonnes by 2050 — well short of the legislated goal.

The two approved projects analyzed in our report — LNG Canada and Woodfibre LNG — would collectively increase carbon pollution by 9.1 million tonnes per year by 2030, further increasing to 10.2 million tonnes per year by 2050. That would leave less than 3 million tonnes per year for the rest of B.C.’s economy — including transportation, buildings, and industry — and make it virtually impossible for the province to meet its 2050 target.

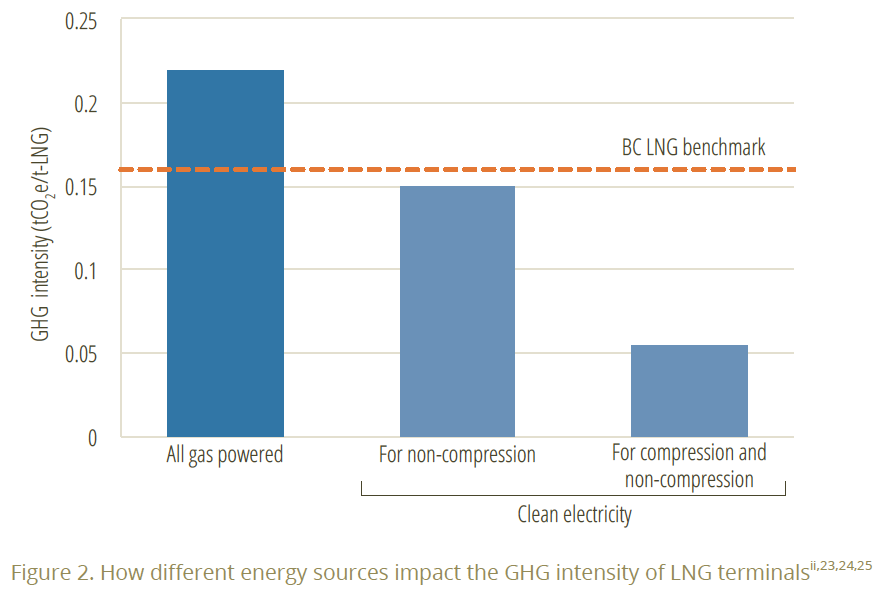

If LNG Canada and Woodfibre LNG were built using best practices and technology — including greater electrification, as B.C.’s Climate Leadership Team recommended — emissions would be halved. However, these combined emissions would still make it very difficult for B.C. to meet its targets without drastically eliminating emissions from the rest of the economy.

Pacific NorthWest LNG could rise from the dead

Pacific NorthWest (PNW) LNG’s cancellation was attributed to prolonged depressed prices and shifts in the energy sector. Prior to the announcement, PNW LNG was among the projects considered most likely to proceed, having secured export, pipeline, facility, and (conditional) environmental approvals, as well as agreements with some local First Nations. However, other First Nations groups and the SkeenaWild Conservation Trust launched court challenges in an attempt to block PNW LNG, citing issues involving the consultation of indigenous communities, impacts on fish habitat, and carbon pollution.

Although PNW LNG is officially cancelled, various permits for the project remain valid. These include a National Energy Board export licence and a positive environmental assessment decision by the Canadian government. Until the permits are forfeited or voided, the project should still be considered a potential LNG development along B.C.’s North Coast.

If the permits for PNW LNG were resurrected by the current or a new owner, the project would make the province’s legislated 2050 climate target impossible to reach. Such LNG export terminals, fully powered by natural gas, are almost four times more polluting per tonne of LNG produced than terminals using clean electricity.

Several policies in place in B.C. are designed to reduce emissions from LNG and associated upstream development. However, these policies fall short of requiring projects to adopt best practices and technologies. They should be strengthened to ensure that, if development proceeds, it is with the lowest impact to the climate.

Maximilian Kniewasser is the director of the B.C. Climate Policy Program at the Pembina Institute, Canada’s leading clean energy think-tank.

Stephen Hui is the B.C. communications lead at the Pembina Institute.

This op-ed originally appeared on DeSmog Canada on August 30, 2017.