Climate change is most often thought of as a future threat, but as many of us know, its impacts are being felt more and more every day. The consequences of major spring flooding and summer wildfires on both sides of the Rockies in the past few years are telling: natural disasters are happening more often, and with greater severity.

These trends are prompting a variety of voices from the business community to chime in on climate policy. As the frequency of extreme weather events has risen, so too have the insurance payouts. Insurance claims due to severe weather, floods, and wildfires used to average a few hundred million dollars a year. Since 2009, however, we have seen a surge, and claims now total over $1 billion every year. Concerned about the exposure Canadians face due to the impacts of climate change, insurers are among those who are speaking out — calling for stronger climate policies and increased investment in measures to help residents adapt to our new climate reality. In this vein, this month’s return to regular increases in B.C.’s price on carbon pollution is most welcome.

In February, the B.C. auditor general issued its analysis of the B.C. government’s performance with respect to managing climate-change risks and meeting climate targets. Its conclusions were blunt: We are unprepared for the risks posed by climate change, we don’t have a plan of action, and we’re not on track to meet our 2050 goal to reduce carbon pollution by 80 per cent. The report pointed out major gaps in adaptation measures (to lessen the severity of climate impacts) and the need to increase mitigation actions (to reduce carbon pollution and limit the magnitude of climate change).

The province’s climate adaptation strategy is nearly a decade old and a refresh is greatly needed. On the mitigation side, the government has committed to developing a strategy to get B.C. back on track to significant carbon pollution reductions. The first major action announced was the return to annual increases in B.C.’s carbon tax, a clean-economy incentive, as of April 1.

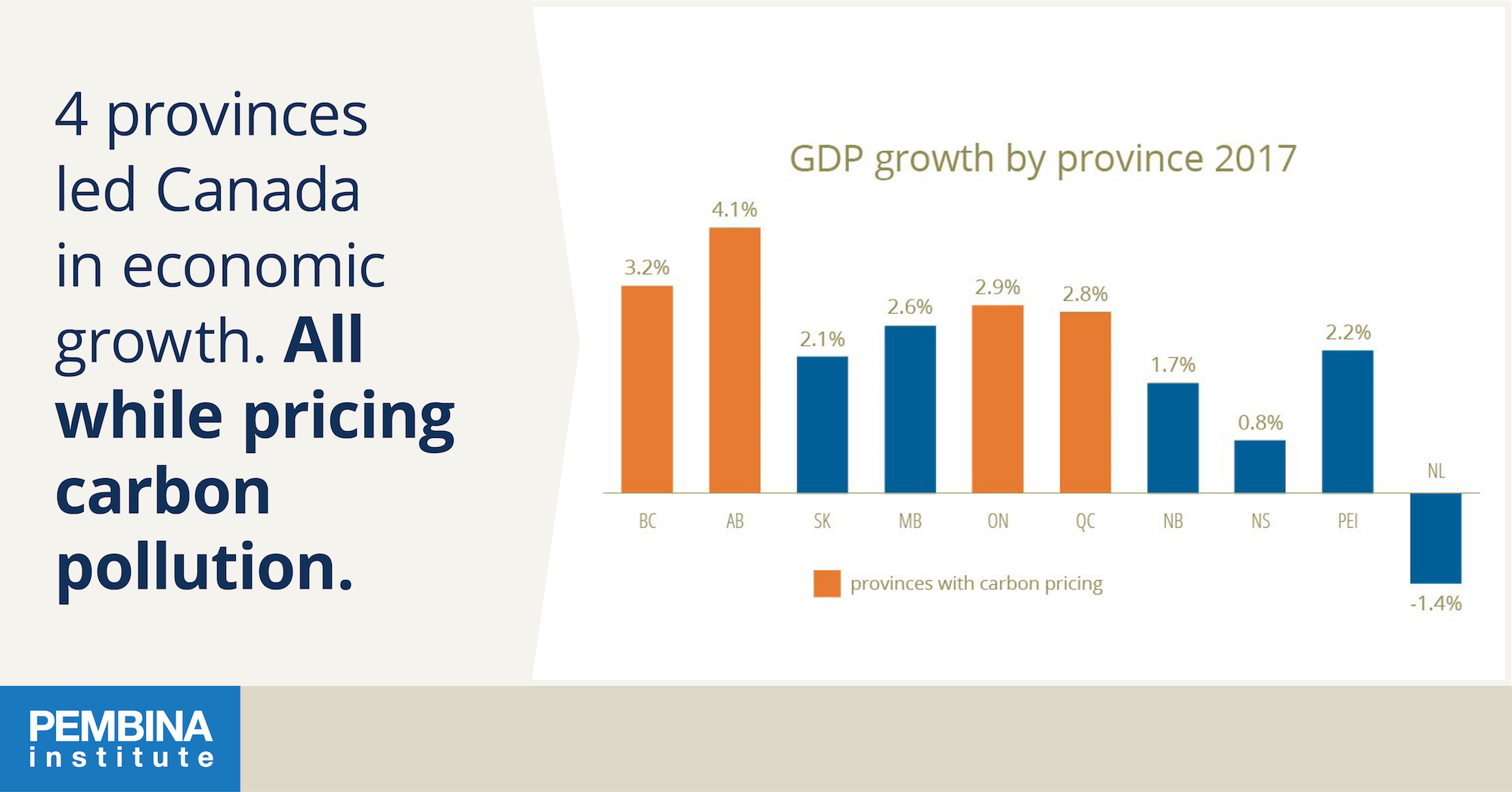

B.C.’s experience shows a carbon tax can work to lower carbon pollution, and pricing this pollution — contrary to what critics say — doesn’t prevent economic growth. Between 2008 and 2011 (from introduction of the carbon tax to the government’s freezing of the carbon tax at 2012 levels), emissions per capita from sources subject to the carbon tax in B.C. dropped by 10 per cent, but only one per cent in the rest of the country. During this time, B.C.’s economic performance (as measured by gross domestic product) was stronger than the national average.

In 2017, pricing carbon pollution became mainstream economic policy in Canada. Carbon pricing systems are in place in Canada’s four largest provinces, representing 86 per cent of the population. Ontario and Québec have a cap-and-trade system linked to California. Alberta has a carbon levy. These efforts are mirrored around the world, with over 40 national and 25 subnational jurisdictions putting a price on carbon.

By January 2019, carbon pollution pricing will be in effect across Canada. However, the carbon pricing systems being implemented also need to ensure all Canadians benefit from moving towards a clean economy. This means taking care to avoid adverse impacts to vulnerable, lower-income, and rural households. It also means putting in place temporary and targeted measures to ensure heavy industry remains competitive in Canada — where we have stronger climate policies — and doesn’t move to jurisdictions without a carbon tax.

After its introduction, B.C.’s carbon tax was lauded internationally as a “textbook” example of how pricing pollution can be effective. But pricing pollution needs to be considered as part of a holistic approach to addressing climate change. For B.C. to re-emerge as a climate leader, the following are required: mitigation and adaptation strategies that reduce the risks and impacts of climate change for British Columbians, a plan for achieving significant emissions cuts, and a strategy to better incentivize B.C.’s transition to low-carbon industries.

Without the whole package, the costs of climate change to all British Columbians will continue to rise.

Aaron Sutherland is vice president for the Pacific region at the Insurance Bureau of Canada.

Karen Tam Wu is acting B.C. director at the Pembina Institute, Canada’s leading clean energy think-tank.

This op-ed originally appeared in the Hill Times (Ottawa) on April 16, 2018.