Like oxygen, nitrogen, and yes, carbon dioxide, summer is in the air. The Pembina Institute took a moment this season to review the federal government’s 25th and most recent filing of Canada’s National Inventory Report (NIR), a detailed publication and data set describing Canadian historical greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The submission of the NIR each spring (according to guidance provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) fulfills a basic reporting requirement under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

As Canada’s full tally of human-caused emissions and removals (sources and sinks) of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases, NIR 2018 is a 500-plus-page tome of meticulously assembled data and analysis compiled by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). The most recent time series data in the NIR always fall two years behind its date of publication, so this year’s version chronicles Canadian GHG emissions from 1990 to 2016. The data are sorted at national and provincial-territorial levels and are helpfully arranged into economic categories — oil and gas, transportation, electricity, heavy industry, and agriculture.

Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada [ECCC], National Inventory Report 1990-2016: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada — Canada’s Submission to the UNFCCC (2018) [NIR 2018].

Notes: Values are given in megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2eq). Total national emissions were 704 Mt in 2016. Synthetic gases include hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3).

NIR 2018 documents what, how much, and where we emit (see Figure 1). The inventory also shows how emissions (measured in megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, or Mt CO2eq) are related to different economic activities and how these relationships have changed over time. As usual, the NIR tells many stories — some new and hopeful, others old and cautionary. Here are three that stand out to us.

1. Going the right direction at the wrong pace

2018 marks the mid-point between 2005, our chosen base year for climate target-setting, and 2030, the target year Canada set to achieve its promised reductions to global GHG emissions under the Paris Agreement. With 12 years left to reach our target, are we on pace to reduce emissions 30 per cent below the 2005 baseline? Although total Canadian emissions have fallen slightly since 2005, unfortunately the most recent national inventory shows no great change in the rate of emissions decline (see Figure 2) — the most immediately material indicator for assessing Canada’s progress on climate. Forget halfway towards Paris — we’re not even halfway towards our now-little-discussed Copenhagen target for 2020. (As noted in the recent joint report from Canada’s Auditors-General, that target is almost certain to be missed.)

Source: ECCC, NIR 1990-2016 (2018), Annexes 10 and 12.

To be sure, if deep decarbonization by mid-century (on the order of 75–90 per cent) is the finish line — as envisaged in the federal government’s Mid-Century GHG Strategy— then we’re headed in the right direction. But we’ll need to move much faster if we hope to reach the 2030 checkpoint that will keep us in the race. While a 10 Mt drop in emissions from 2015 to 2016 was a promising sign (see Figure 2), over the last five years, Canada’s average reduction in the national total was only 1 Mt per year. At that pace, we won’t achieve our Paris Agreement target until the beginning of the twenty-third century (2209, to be precise). However, there’s reason to hope.

Sources: ECCC, NIR 1990-2016, Part 3 (2018); Canada’s 3rd Biennial Report & 7th National Communication to the UNFCCC [3BR] “with measures” and “with additional measures” scenarios; Canada’s 2016 GHG Emissions Reference Case.

From 1990, which is the beginning of the official record, emissions are up 16 per cent (101 Mt). But relative to our 2005 base year, they’re down nearly 4 per cent (to 704 Mt in 2016). Because the most recent data point in the current inventory is from 2016, it’s too early for the reductions anticipated from the many climate policies currently under development (via the Pan-Canadian Framework, released in December 2016) to be reflected in the historical record. But substantial carbon reduction outcomes can and will be gained through the various mitigation strategies being pursued by federal and provincial governments, including the national price on carbon, the accelerated coal phase-out, regulations to reduce methane released from oil and gas production, and a national clean fuel standard to lower the carbon intensity of fuels used in transport, buildings, and industry.

In Figure 3, the “with additional measures” scenario (dotted green line) shows the federal government’s estimate of where the full suite of developing federal and provincial efforts will take us by 2030. That projection, which leaves a 66 Mt gap to Canada’s target, still shows considerable improvement on previous estimates of Canada’s future GHG trajectory (dashed grey lines) — though it relies on 59 Mt of reductions secured through the purchase of international allowances under the Western Climate Initiative (WCI), of which Ontario and Quebec are members. These reductions are currently in danger, given the newly elected Ontario government’s stated intention to dismantle cap-and-trade and withdraw from WCI.

2. Power check: the low-carbon grid is here to stay

There’s a special place in our hearts for Annex 13, the very last section of the NIR, which presents key statistics about Canada’s electricity generation portfolio and related GHG emissions. Canada is fortunate to have a power supply mix that is already quite low-carbon: our abundant hydropower installations, existing nuclear facilities, and other renewable assets (including wind, solar, and geothermal) respectively generated 60 per cent, 16 per cent, and 5 per cent of total national electricity supplied in 2016. As a natural leader in this space, Canada has a special responsibility to push the frontier in demonstrating what a deeply decarbonized electricity sector really looks like. It’s well known that fuel-switching to decarbonized electricity is fundamental to achieving deep domestic and global emissions reductions. The shift to low-carbon power not only reduces the climate impact of an important and historically high-emitting industrial sector, but also enables further reductions in other sectors through end-use electrification. It makes a big difference whether an electric vehicle is powered by coal plants or by cleaner sources.

Having set an informal, non-binding target of 90 per cent electricity from non-emitting sources by 2030 — part of Minister McKenna’s announcement of the accelerated federal coal phase-out in late 2016 — Canada is making strides toward that aim. While we’re still some distance away — nearly 82 per cent of generation was non-emitting in 2016 — it’s worth noting that the carbon-intensity of the national grid has fallen significantly from its historical high in 2000 (Figure 4).

Source: ECCC, NIR 1990-2016 (2018), Part 3, Annex 13, Table 1.

Since then, driven by Ontario’s coal phase-out, the national average generation intensity (which measures the emissions intensity of electricity as it is delivered to the grid) declined by 100 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilowatt-hour produced. Consumption intensity (which measures the emissions intensity of electricity as it is delivered to the consumer, and so captures line losses and additional emissions from transmission and distribution equipment) fell 120 g CO2e/kWh to a final level of 150 g CO2e/kWh. The International Energy Agency has calculated that meeting the 2-degree minimum temperature goal established in the Paris Agreement will require the emissions intensity of power generation to have a global average of at most 100 g CO2e/kWh by the late 2030s. Since we know both that Canada’s already ahead of the curve, and that we need to go even further, policy-makers should ask themselves: at what point do we consider the Canadian grid to be deeply decarbonized? And how can we model action for the world?

It’s true that the national averages referred to above to some extent mask wide disparities between provinces: coal-fired Saskatchewan’s current consumption intensity indicator is 330 times greater than hydro-powered Manitoba’s. But the overall Canadian trend is encouraging and, as more and more coal plants go offline, projected to deepen (see Figure 4). In fact, the deepening trend is driven not only by the Alberta and federal 2030 coal phase-out deadlines — although these policies’ contributions will be large — but also by a strong mix of ongoing provincial electricity policies, including renewable portfolio standards in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick (40 per cent of supply by 2020 in both provinces), a generation capacity target in Saskatchewan (50 per cent by 2030), and 5,000 MW of competitive renewable procurement in Alberta (targeting 30 per cent of supply by 2030).

3. Erased gains mean we’re running in place

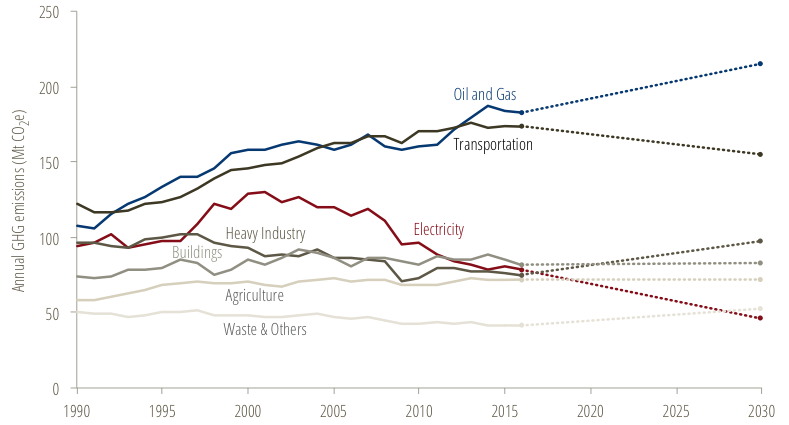

Unfortunately, for all the progress we’ve made in the electricity sector, we made little in others. Since the turn of the century, steady reductions from electricity have been entirely offset by growth in our top two emitting sectors: transportation and oil and gas (see Figure 5).

Source: ECCC, NIR 1990-2016 (2018), Part 3, Annex 13; projections from Canada’s 3rd Biennial Report (2017) “with measures” scenario.

In the transport sector, which generated fully one-quarter of Canadian GHGs in 2016, on-road vehicles are the dominant source of carbon emissions. Since 2005, the number of vehicles on the road in Canada has grown 38 per cent, especially in the light- and heavy-duty truck categories. This increase, and consequently that of kilometres driven, has been the main factor driving emissions growth in the sector.

Source: ECCC, NIR 1990-2016 (2018), Part 3, Annex 12.

The emissions profile of Canadian oil and gas — our highest-emitting sector, at 26 per cent of the national total — includes fugitive, industrial process and combustion-related emissions (stationary combustion, off-road transportation, and utility and industrial generation of electricity and steam). From 1990 to 2016, total crude oil production increased 133 per cent; more than 90 per cent of this production growth occurred in Alberta’s oilsands, spurred by the development of newer “in situ” extraction processes like steam-assisted gravity drainage. Higher production levels translated into substantial emissions growth: over the whole record, oilsands emissions alone grew 367 per cent to 72 Mt. Put another way, the climate impact of the oilsands subsector is now roughly equal to that of all other Canadian heavy industries (cement, iron and steel, mining, etc.) combined.

With the latest government projections showing continued growth in oil and gas GHGs and only modest GHG reductions in transport, serious questions remain about whether and how Canada will be able to meet its 2030 climate target. That’s why continuing to implement effective climate policies, including carbon pricing, regulation on oil and gas methane, tailpipe emissions standards for passenger and heavy-duty vehicles, and support for zero emissions vehicles, remains vital to Canadian climate action — and to the ability of Canadian industries, including the oilsands, to compete in an increasingly carbon-constrained global economy.