This is the second article in a three-part series based on the findings of the report Accelerating Market Transformation for High-Performance Building Enclosures. Read Part 1 and Part 3.

Both north and south of the border, the new U.S. administration’s position on energy efficiency was already a source of concern for clean economy advocates prior to their announced intention to withdraw from the Paris Accord. Canada is still recovering from a decade of inaction and regression on environmental issues under the previous government. The current Canadian government is making progress on the climate file — setting a minimum price on carbon and charting a pathway to net-zero ready building codes by 2030 — but much remains to be done.

Both north and south of the border, the new U.S. administration’s position on energy efficiency was already a source of concern for clean economy advocates prior to their announced intention to withdraw from the Paris Accord. Canada is still recovering from a decade of inaction and regression on environmental issues under the previous government. The current Canadian government is making progress on the climate file — setting a minimum price on carbon and charting a pathway to net-zero ready building codes by 2030 — but much remains to be done.

Fortunately, in both countries, subnational governments have significant jurisdiction over the building sector. Some states, provinces, and local authorities have shown leadership in policy design, for example: New York City’s policy requiring new public buildings to be 50% more efficient than the average for each sector, their intention to increase code stringency significantly over the next few cycles, and many other incremental measures like their thick wall exclusion for high performing buildings; the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency’s competitive funding for new affordable housing granting points for Passive House certification, or Baltimore County’s High Performance Home tax credit. California’s vision to make new residential and commercial buildings zero-net energy (ZNE) by 2020 and 2030, respectively, has lead it to draft some of North America’s most ambitious stretch codes (CALGreen) and building codes (Title 24).

Readers in the U.S. are probably familiar with these examples. But some might be less familiar with the Canadian scene, so we’ve dedicated this article to sharing progressive policies recently put into place on Canada’s West Coast.

Vancouver: epicenter of the Passive House boom?

The city of Vancouver is a hot spot of Passive House activity, with at least 12 multi-unit mid-rise residential projects currently in development. When completed, these will account for a quarter of all of the Passive House square footage we could inventory (i.e. including all certified projects and our non-exhaustive [and geographically biased] survey of projects aiming for certification). This was supported by city hall, which attempted to remove barriers to Passive House by providing certified projects with floor space exclusions for thick walls, height and set-back relaxations, and an alternate compliance path to meet rezoning requirements for increased density. The city also trained permit reviewers and inspection staff in Passive House to reduce possible barriers to innovative designs and streamline processing.

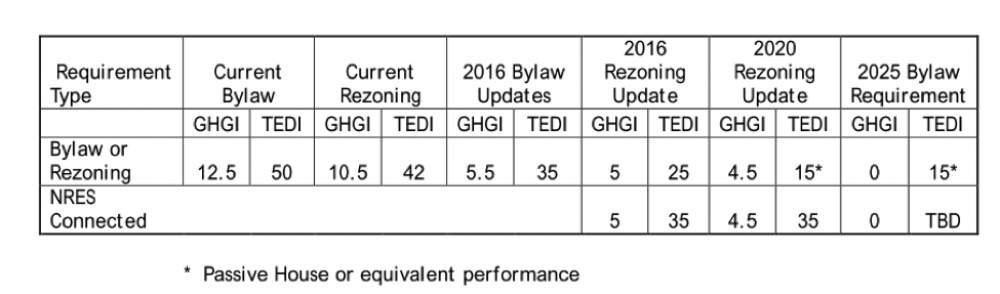

But this was only the beginning. The City of Vancouver’s Zero Emissions Building Plan charts a course for a 90% reduction in emissions from new buildings by 2025, and achieving zero emissions for all new buildings by 2030. The plan sets a course for all new multi-family buildings six storeys and under to be built to near Passive House levels of performance by 2020 (i.e. requiring a thermal energy demand intensity no greater than 15 kWh/m2/year; see Figure 1). An intermediary target of 25 kWh/m2/year was adopted (alongside a prescriptive compliance option) in the latest revision to the building bylaw coming into force in March 2018. As a result, emissions from low-rise multi-family buildings will be reduced by 40% to 55%. Homeowners and renters will see energy savings of $2.8 million (CAD) over the next five years, and the net cost of ownership (including mortgage and energy payments) for new owners will be realized from day one.

The city has also committed to build all new city-owned projects to the Passive House standard (unless deemed unviable). A fire hall and a social housing project are new Passive House projects underway.

Figure 1. Targets for low-rise MURBs in the City of Vancouver’s Zero Emissions Buildings Plan

Note: GHGI: Annual greenhouse gas emissions intensity, in kg-CO2e /m2. TEDI: Annual thermal energy demand intensity, in kWh/m2. Bylaw requirements apply to all low-rise MURBs, rezoning requirements apply to projects seeking to increase density beyond current zoning requirements for their site. Historically, more than half of new floor area built in Vancouver requires rezoning. See p.17-18 of the plan for targets for high-rise MURBs, and offices.

British Columbia: taking stretch codes to the next three levels

In the meantime, the Province of British Columbia is also moving forward with plans for more efficient buildings. Its latest provincial climate plan, while generally lacking in ambition and insufficient to meet the province's legislated carbon reduction targets, did contain some promising building policies. This includes a commitment for all new construction to be net-zero ready by 2032, the establishment of incentives for high-performance new construction, as well as increased support for training and capacity building.

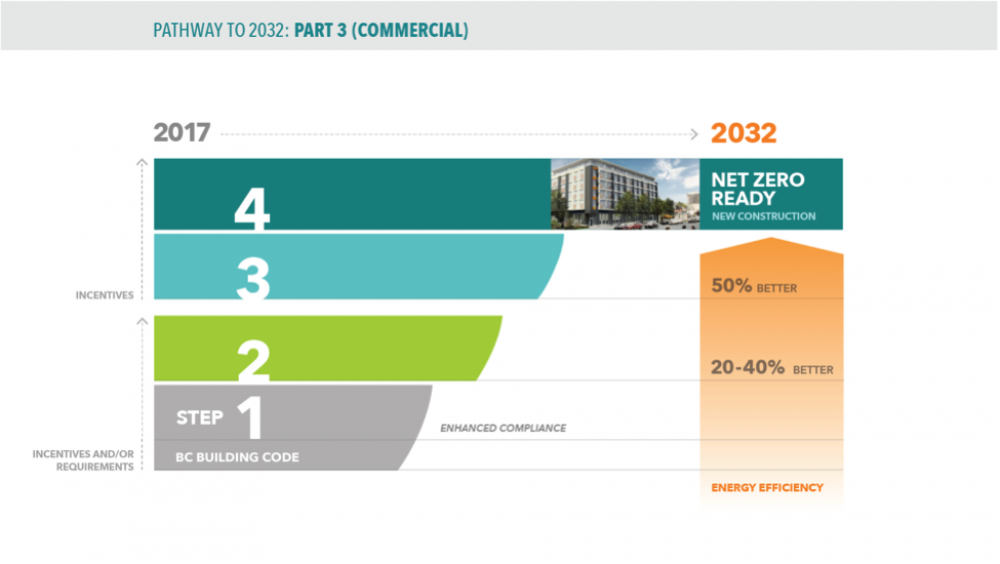

The plan also confirmed political support for North America’s first multi-tiered energy stretch code, dubbed the Energy Step Code. This opt-in, performance-based standard will provide a unified framework for local government to incent or require energy performance beyond code minimum. It includes four performance steps, the first step requiring energy modelling and air-tightness testing (but no additional performance gains beyond base code), and the last step requiring performance levels matching the international Passive House standard (i.e. a thermal energy demand intensity no greater 15 kWh/m2/year)(Figure 2).

The Energy Step Code thus provides a four-step roadmap between current building practice and the net-zero ready goal. It also confirms a consensus towards an “envelope-first” approach, and sets Passive House levels of performance as the desired end goal. The Energy Step Code will allow leading municipalities to devise policies and incentives to move both the bulk and the leading edge of the market transformation bell curve, to prepare the industry not just for the next code cycle but also for the more profound changes needed for high performance construction to become the norm by 2030.

Figure 2. British Columbia energy step code tiers for Part 3 buildings (i.e. commercial, mid to high rise residential)

As we will discuss in the last article in this series, the success of this transition requires a shared vision of the end goal, and government support for the leaders who are building to Passive House performance today.

Vision and support from the public sector will be needed for this Passive House (r)evolution to bloom into a new normal. A friendly competition between subnational governments on both sides of the border could be an invigorating stimulus.

We’ve dropped our cards. New York, show us what you’ve got.

Tom-Pierre Frappé-Sénéclauze is a senior advisor with the Buildings and Urban Solutions Program at the Pembina Institute, a non-profit think-tank that advocates for strong, effective policies to support Canada’s clean energy transition. He is the lead author of the report Accelerating Market Transformation for High-Performance Building Enclosures.

This article originally appeared on Insight, the blog of the Building Energy Exchange, ahead of the New York Passive House 2017 Conference & Expo.