Canada, the energy used in homes and buildings — for heating and air conditioning, hot water and running appliances and office equipment — accounts for nearly a quarter of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. Left alone, inefficient, leaky buildings will suck energy and spew emissions for several decades.

Buildings have long lifespans — longer than those of power plants, cars and appliances. The consequences of inefficient buildings can last generations, so we have some important choices to make today about how we build and maintain them. A bold, long-term commitment to well-built, nearly-zero-energy buildings — which create almost as much energy as they consume —will generate economic, health and environmental benefits for Canadians for years to come.

Many home and business owners have taken simple actions to improve the energy efficiency of residential and commercial buildings, such as replacing weather-stripping around windows and doors, insulating roofs and walls and swapping out old boilers and furnaces. But time is not on our side.

Sweeping changes are needed to make high-efficiency buildings the norm rather than the niche. Low-cost, high-return opportunities are all around us, in our homes, office towers, schools, factories, hospitals and more. For policy-makers looking to cost-effectively and rapidly cut carbon pollution, building improvements are the low-hanging fruit. In fact, in the building sector, we could and should be aiming to exceed Canada’s national emissions reduction targets.

There are two specific areas where we think the federal government, in collaboration with its subnational counterparts, could create clean economic growth by advancing the construction of healthy homes and buildings. First, drafty old buildings need to be modernized for the 21st century — the “clean growth century”. This can be done by creating a retrofit strategy that includes revising building codes to address retrofitting and encourages actions like fixing airtightness and heat loss; installing better windows, doors and insulation; and upgrading our heating, cooling and ventilation systems. Second, new buildings need to be constructed to the most energy-efficient design and construction standards.

Retrofits: Making the old better than new

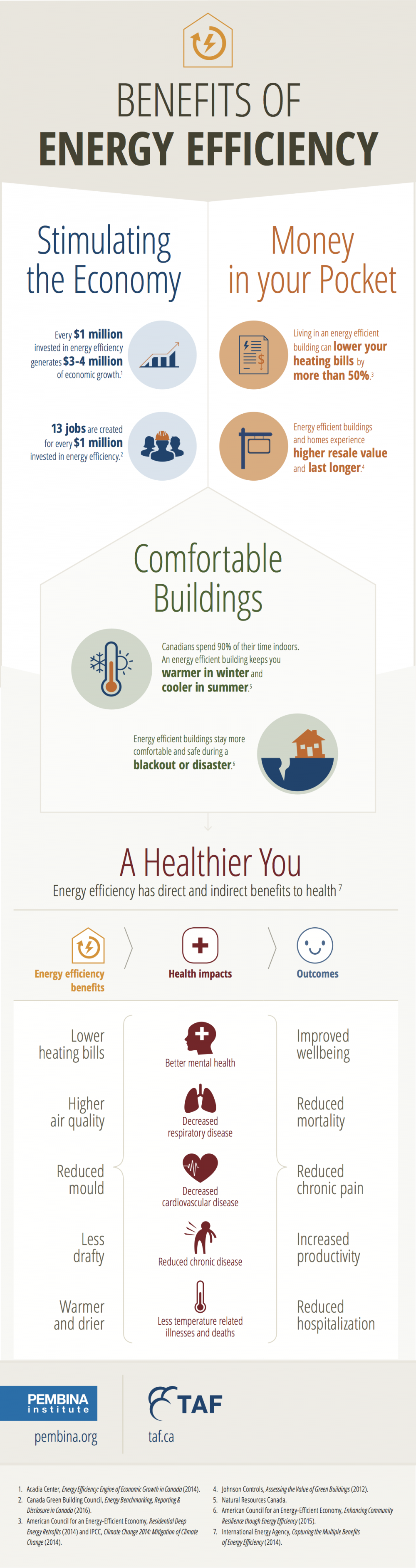

Canadians spend 90 percent of their lives indoors. It should be no surprise that the quality of our indoor environments can have a major impact on our health and well-being. Replacing leaky windows and insulation and improving ventilation can address healthand comfort-related problems linked to cold air drafts, excess moisture and mould — not to mention saving energy. Several studies indicate that health benefits could represent up to 75 percent of the overall benefits of energy efficiency retrofits.

Programs and regulations that promote energy efficiency measures will not only reduce carbon pollution significantly; they will be a powerful economic driver of Canada’s clean growth century. Innovation in the building sector can demonstrate that reducing emissions and clean growth are achievable. Green buildings already account for nearly 300,000 jobs in Canada. That’s more than in oil and gas, mining and forestry combined. Energy efficiency programs are great local job creators: they employ people to manufacture and install windows, put in rooftop solar-thermal hot water systems, blow insulation and so on.

A 2014 Acadia Center report commissioned by Natural Resources Canada examined the impact of Canadian energy efficiency policies on GDP and job creation. The researchers concluded that energy efficiency programs would spur a net increase in GDP, contributing $230 billion to $580 billion to the economy between 2012 and 2040. In fact, each $1 spent on energy efficiency programs in Canada would yield a GDP increase of between $5 and $8. Every $1 million invested in efficiency programs generates 30 to 52 job-years.

New construction: An opportunity for innovation

The technologies and standards needed to create near zero-energy buildings are already being deployed. If Canada is to compete in the clean growth century, we need to deploy these technologies and strategies at scale, then identify opportunities where Canadian innovations can push the global market for clean buildings forward.

The Pan-Canadian Framework set a target for all new buildings codes to be “net-zero energy ready” by 2030. The amount of energy used in such buildings on an annual basis could be generated on site by renewable energy systems (such as solar panels). Vancouver has gone a step further; its Zero Emissions Building Plan means most new buildings in the city will have zero operational greenhouse gas emissions by 2030.

Nearly-zero-energy buildings are rare in Canada today, but they are already a US$14-billion market in Europe. Under the European Union’s 2012 Energy Efficiency Directive, all new buildings must be nearly zero energy by the end of 2020; all public buildings must reach that standard by the end of 2018. Encouraging early adoption of such standards in our country (through incentives and financing, for example) will stimulate the marketplace to facilitate the transition to having all homes and buildings built to meet them.

Such buildings, by design, will last longer, use less energy, cost less to run and require less maintenance. Societal benefits such as well-being, health and equity can also be increased. For at least one million Canadians who spend more than 10 percent of their income on their utility bills, meeting basic energy needs is a substantial burden. Prioritizing investment in energy efficiency in low-income and social housing provides particularly valuable societal benefits.

To achieve success, the vision of the Pan-Canadian Framework must be backed with a long-term commitment. It could include multi-year funding for program implementation, adequate resourcing for the departments responsible and government leading by example. Success also requires an accountability mechanism to ensure investments get us on track to meeting our 2030 and 2050 targets for reducing carbon pollution.

A bold shift to energy-efficient buildings will create local jobs, attract investment, strengthen the foundation of the innovation economy and benefit families and communities across Canada.

Elizabeth McDonald is president and CEO of the Canadian Energy Efficiency Alliance.

Julia Langer is CEO of The Atmospheric Fund.

Jay Nordenstrom is the executive director of NAIMA Canada.

Karen Tam Wu is the B.C. associate director and director of the Buildings and Urban Solutions Program at the Pembina Institute.

This Clean Growth Century Initiative article originally appeared in Policy Options (version française).