Canada’s long-running carbon-pricing debate took a dramatic turn when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau kicked off Parliament’s debate on ratifying the Paris climate accord. While growing pains may dominate the headlines in the near term, the commitments laid out in his speech will reshape the Canadian government’s role on climate change – for the better – for years to come.

Mr. Trudeau’s carbon-pricing plan levels the playing field from coast to coast to coast. It ensures provinces and territories that have been slow to price carbon pollution will catch up. It also requires early-moving provinces to strengthen their systems. In effect, the national logjam has been broken by pushing everyone outside their comfort zones.

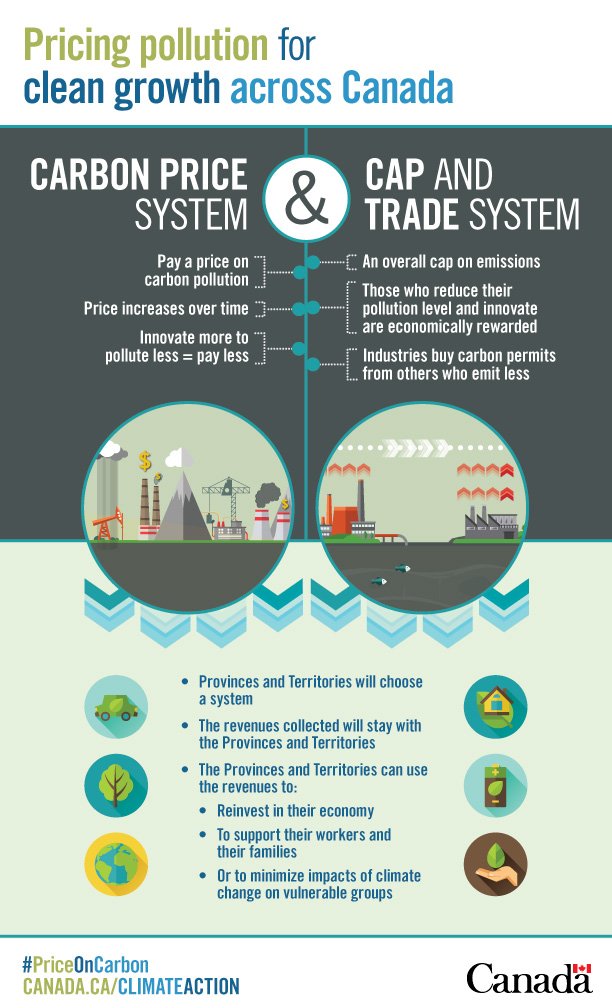

The new plan requires all provinces and territories to meet a minimum carbon price by 2018, which then rises yearly until 2022. The game changers are that only carbon taxes and cap-and-trade systems qualify, and that if any province chooses not to meet the benchmark, the feds will do it for them.

Cap-and-trade involves setting an economy-wide carbon pollution limit, which is lowered over time. Meanwhile, companies are allowed to buy and sell emissions allowances, which gives them a market incentive to reduce their carbon pollution.

The politics and substance of the plan are significant.

In terms of the politics, calls for a national carbon price have echoed across Canada for two decades, but the political will never emerged under successive Liberal and Conservative governments. The lack of leadership in Ottawa created a vacuum that provinces began to fill: B.C. and Alberta implemented carbon taxes; Ontario and Quebec brought in cap-and-trade systems. These efforts helped Canadians get used to the idea of carbon pricing and provided real-world contrasts to the carbon-pricing scaremongering that continues to exist.

But even though 80 per cent of Canadians live in provinces that price carbon pollution, national progress remained elusive. Despite a successful economic and environmental track record, B.C.’s carbon tax has been stagnant since 2012, and Premier Christy Clark has said it won’t be increased until the rest of the country reaches the same level. Without federal leadership on the issue, the prospects of that condition being met were dim.

Not surprisingly, being pushed outside of their comfort zones has elicited negative reactions from some provinces. The environment ministers of Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador stormed out of a meeting with their federal counterpart, Catherine McKenna, in protest. Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall called the plan a “betrayal” of pledges to let provinces set their own environmental agendas.

These complaints ignore the amount of flexibility that provinces will have under the new plan. As long as their ambition is comparable, provinces can choose between a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system. If a province is starting from scratch, it has until 2018 to put the pieces in place. Provinces that already have carbon prices have even longer to meet the new standards.

More importantly, each province will decide how to invest the revenue generated by carbon pricing – a figure that will be in the billions nationally. As demonstrated by the decisions provinces have made regarding carbon pricing revenue, there’s no single right answer. Quebec has used cap-and-trade revenue to invest in green projects; B.C. has used carbon tax revenue to lower other taxes. Empowering the provinces to continue making those decisions gives them the flexibility to tailor the use of revenue to their specific opportunities and challenges.

Beyond the politics, it’s important to not lose sight of the carbon price itself and the incentive it will provide to reduce carbon pollution. While the $10 per tonne price floor in 2018 is nominal (about two cents a litre on gasoline), the increase to $50 per tonne by 2022 is more substantive. This clear signal will help make renewable energy and energy efficiency a more affordable choice for households and businesses.

For example, at $50 per tonne, an average Canadian household could save over $1,200 per year in energy and carbon costs by driving a plug-in hybrid instead of a standard new car. The more Canadian households and businesses take advantage of those types of solutions, the stronger Canada’s clean energy companies become. That will better position them to capitalize on the growing global demand for clean energy – a sector estimated to be worth $1.3-trillion in 2014.

The new carbon-pricing plan represents a ray of light cutting through the cloud of skepticism that has hung over Canada’s efforts to fight climate change. With so many challenges remaining – wrestling with major new sources of carbon pollution like Petronas’s Pacific NorthWest LNG, phasing out coal, or reducing energy use in buildings, to name just a few – the work to get on track for Canada’s targets is just beginning. The carbon pricing breakthrough can be a launching pad for the bigger successes the country still needs to achieve.

This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail.